Review of Rebel Moon, Part One: A Child of Fire

Rebel Moon is irredeemable garbage. I rarely see scathing reviews anymore, but this deserves a properly scathing review. I’ll do my best to describe in detail why this movie is, to put it lightly, deplorably bad.

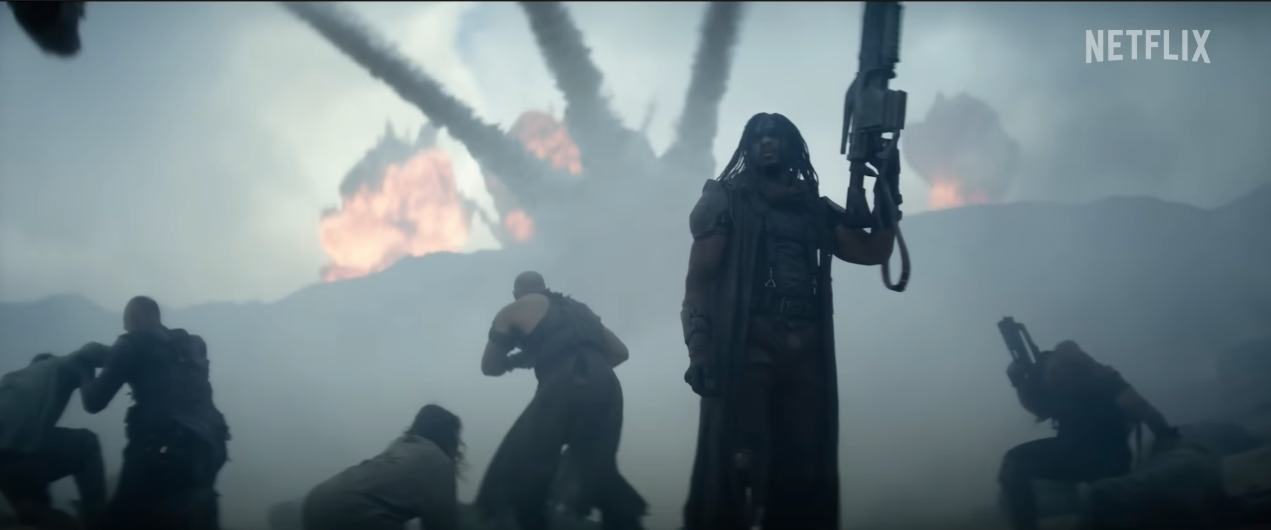

The Poster

I came into the film expecting nothing but hoping it would be decent. I’m not the biggest fan of Snyder’s films, but there are a few I’ve enjoyed, and the trailers for this didn’t’ look bad.

Alas, I’ve been wrong before.

Shall we dive in?

From the bloated title to the bloated runtime, down to the bloated exposition and flashbacks, this movie is the budget-wasting equivalent of walking into a casino with your life savings and blowing it all on a spin of roulette.

Before proceeding, I should note: The film was originally a Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977) film pitch according to various sources, and that fact is not hidden at all. The opening crawl of exposition has been turned into a voice-over by Anthony Hopkins. The opening scene of an enormous ship in space? Still here – this time it’s coming out of a space vulva – and it’s far less interesting. I’ll comment on other nods to Star Wars throughout the review, as there are quite a few and they’re not hard to spot. Additionally, there are plenty of details that seem to be stripped from other popular fantasy or sci-fi films, though far more generic here.

The film starts with a shot of a woman tilling a gorgeously backlit field. This is, in fact, the only shot in the film I enjoyed. It’s colorful, complex, and gives us something that feels original but familiar. Some stiff dialogue ensues as we meet the heroine, but despite the plodding back and forth, it seems we’re on our way to a story. We’re taken into the town as its people prepare a celebration for the harvest, and the town “Father” (played by Corey Stoll) calls for everyone to…go home and have sex. He then carries off his own lover to presumably do just that. I was initially willing to overlook this strange start. After all, it’s science fantasy. After finishing the movie, however, it’s clear that this scene is the beginning of a borderline unintelligible script.

The next main sequence is an egregiously long back-and-forth conversation introducing our main bad guy (Ed Skrein) to the Father (Stoll). I gathered, based on the attention given to the scene, that this was supposed to be rife with tension, deceit, and verbal gymnastics as they expertly navigated etiquette and wrestled what they wanted from the other. Yet, the writing is so dull, the shots so lingering, and the events so contrived that any tension was killed long before the sequence comes to a climax. The bad guy kills the Father as expected, and we lose one of the only decent performers in the film. The scene feels like an homage to the opening of Inglorious Basterds (Quentin Tarantino, 2009), in which the audience understands the clear threat of Nazism due to historical context and superb blocking, acting, and dialogue, but Rebel Moon lacks any of the qualities that allowed Tarantino’s scene to succeed.

Like…are you kidding me with this mountain?

Personal Note: In the background of the village on the main location, there is a single mountain with a massive waterfall coming down the side, which is neither how mountains nor waterfalls work, I don’t care if it’s science fantasy. It reminded me of when a child draws a picture and decides to put a mountain and a pretty waterfall and a rainbow with clouds in the corner. It’s nice when kids do it, not so much in a film with a budget of $166 Million. And there wasn’t even a rainbow in the corner.

Suffice to say: The mess of a script, by twenty or so minutes into the film, has become apparent.

Troops of military personnel are stationed on the main moon after the town is given an ultimatum by Ed Skrein’s big bad, Noble. And here we find the best example of this movie’s poorly written, random amalgamation of ideas – which has been labeled a script.

In the military unit there’s an arrogant, violent second-in-command, a harsh-but-fair commander, and a low-ranking benevolent martyr-type, as well as a victim of circumstance in the form of a robot. Are these official character archetypes? No, but they’re certainly well-known tropes. We meet this band of disposable characters in an infernally long sequence that could have been cut altogether. I’ve described the sequence and some of its many infuriating details in red.

TRIGGER WARNING: Red text contains references to rape, as depicted in the film.

The arrogant second-in-command is explaining and expositing to the commander about military robot history in the most disrespectful manner imaginable. A few questions came to mind which immediately took me out of the film.

· Why is he getting away with this tone when speaking to his supposedly rough-and-tough superior?

· Why would a lower ranking soldier be aware of this information and not his superior?

The answer to both is poor writing.

After this lengthy expository dialogue, the second-in-command makes a cringe-worthy show of force, to demonstrate how the robot won’t fight back – this could’ve replaced the exposition entirely.

The low-ranking martyr steps in to help and gets threatened. The commander signals that he’s harsh-but-fair by taking control of the situation and letting the robot clean itself up, then telling the second in command to help do manual labor. This is expected of the trope, and we’ve seen it all before, but someone here desperately needs a screenwriting lesson about “show, don’t tell”.

As if it wasn’t enough to victimize the robot, Snyder also depicts the victimization of a young girl as the soldiers talk extensively about how they’re going to rape her while she’s held captive. So gritty and dark of him! And yes, we are still spending time with these expendable characters.

Kora kills some expendable soldiers to prove she’s heroic.

I have a lot of issues with this entire scene, not least of which is that it’s written as a “Save the Cat” for the hero to prove herself as being a good person. Because of this, the soldiers are written flatly as vile and inhumane to justify killing them remorselessly. The martyr soldier was obviously written in to offset this flatness and pretend there are multiple dimensions to these disposable characters. This addition to the script actually creates more problems, which I’ll get to in a moment.

Additionally, the farm girl is written flatly as a victim to set up the scenario. No agency is given to anyone in the situation except, arguably, the heroine. The writing is contrived, formulaic, and aimless. There are no stakes in sight for the audience, who surely understands that they will not be witnessing the brutal rape and murder of a young woman on-screen in a PG-13 film (thank goodness).

So, the martyr of the group stands up for the farm girl. What does this accomplish, and why does it present issues for the script? The character’s intercession accomplishes two things: it pauses the action long enough for the heroine to intervene, and it redeems the imperial soldiers by proving there are some good ones among them. Both accomplishments are overridden by the slew of questions that come with the character’s decision to step in:

· How did this guy remain in the military without these clear differences in ideology arising before now?

· Is there any reason to show that the military in the movie has individuals who are “good” aside from an infantile attempt to portray that “there’s good on both sides”?

· If the rapist brutes are fodder for the hero, why make one of them decent if we never see him again?

· How has this military been so effective if they are constantly brutalizing and fighting themselves? (In fact, the writers seem to have a very loose grasp of how tactics, strategy, and armies function. I’m no expert, but I’m pretty sure decent organization has quite a bit to do with success.)

Most of these questions can be answered by lazy writing. There wasn’t thought put into the scene or the characters. The writers set out to make the scene do something specific, without worrying about repercussions or immersion. Consequently, the writing feels driven by the will of the writers rather than the will of the characters, which means there is little to no immersion or emotional connection to be found for the audience. But wait…there’s still more. The writing is not just lazy, it is actually quite conceited and self-praising. Let’s go to the next scene for context.

In one of the most laughable demonstrations of the writers’ self-aggrandized vaunting: The commander who virtue-signaled to the audience earlier, by stepping in for the robot, decides to step in again. This time, it’s to prevent the rape of the girl. The film really wants to make you feel as if there is some sort of suspense in this moment, as it relishes a brief pause in the action before the commander speaks again. He’s stepped in because he wants to rape the girl first. Even Game of Thrones’ Season 8 would be proud of this example in sUbVeRtInG eXpEcTaTiOnS. The writers believe themselves to be cleverly misdirecting and shocking the audience, but in fact have only succeeded in wasting our time, as it turns out much of the movie is devoted to doing.

This situation with the farm girl brings up the unanswered mystery of the robot, voiced by Anthony Hopkins, which is one of the more compelling plot points in the movie. Or it would be, if the movie didn’t drop it entirely. It is explained in great detail during both spoken dialogue and narrated flashbacks that an elite guard of robots laid down their arms forever when the king was killed. Ignoring the lazy storytelling for a moment, there are questions that arise from this backstory:

· The king is shown to have been a fascist conqueror later in the film, and the military was just as ruthless when he was in power. Why would the robots stop fighting when he was killed?

· The robot explains to the farm girl– in more spoken exposition – that the robots all hoped the princess would free them from their brutal existence. Weren’t they made to be soldiers? If so, why are they sentient?

· If the princess was the one they fought for, why is it specifically explained that they laid down their arms when the king died?

· I’m actually interested in the robot, but the robot literally runs away after helping the heroine during the farm girl captive scene (I’m assuming for a future installment) Why were we given this deafeningly boring movie, instead of a movie exploring the robot?

We’re not even halfway through, but we’ve wasted time setting up expendable side characters for the heroine to kill and the backstory of a character we never meet again in this film. Don’t worry, the main character of the movie, Kora (played by Sofia Boutella) eventually gets not one, but TWO exposition-dumping, narrated flashbacks. Exposition is necessary, spoken exposition is not. Show. Don’t. Tell. Snyder may have been better off writing a series of fiction novels and allowing them to be adapted to film by someone else, if we’re giving constructive criticism.

Personal Note: Films don’t need baseless violence, sex, or even *gasp* sexual violence to be dark and gritty. All those things can be well written, well incorporated, and well characterized. Though you wouldn’t know it by watching this film.

Charlie Hunnam’s character.

Moving on, some of my timeline of the film may be off for certain plot points, because it was tough to pay attention.

Next, we get a cantina scene to convey the Star Wars of it all – there’s even a guy with a pig-like face to start a bar fight! Unfortunately, the scene feels less like an homage and more like a cheap knock-off. I’m not a massive Star Wars fan but I do know my Star Wars. Lucas’s films rarely waste time with meaningless engagements. The purpose of the cantina scene in Star Wars is to show (something we’ll never get in Rebel Moon, apparently) several key developments in the hero’s journey:

1. The cantina is the symbolic threshold for Luke as he crosses into a new world on the hero’s journey.

2. The cantina gives us proof that Kenobi is not just a crazy old man but a powerful, dangerous sage.

3. The cantina brings the hero into contact with two characters who will be integral going forward: the smugglers Han Solo and Chewbacca. (This is the only thing Rebel Moon manages to copy)

4. The cantina shows the audience the broad scope of the fantastic and strange world of creatures and aliens they’ve entered.

Whereas Star Wars managed all these, Rebel Moon misses the mark on meaningful progression and gives us a gunfight sequence instead, with dialogue so stiff it may as well have been one of the casualties. The scene can’t even be given merit for introducing Kora as formidable, because we already received a scene showing her fighting skill.

My preoccupation at this point in the movie was: how are these guns working? Do they melt things? Sometimes. Do they poke holes in things? Occasionally. Our hero hides behind a wooden table which takes some full-on laser fire like a champ, but pig-guy gets a hole through his skull. Previously, the skulls of the military goons (who were shot in the head at point blank range) remained intact with no holes. I’d just like some consistency. (With a quick Google search I found the guns to be called “lava-cork guns”. Do what you will with this information.)

The fact that I was focused on this detail speaks to a larger problem: plot and character are non-existent. In fact, Kora and the farmer she’s traveling with – Gunnar (played by Michiel Huisman) – exchange stilted dialogue that confirms she is making this up as she goes, which exactly sums up the writing.

Immediately after the gunfight, a shady thief (Charlie Hunnam, who witnessed the whole fight but didn’t help till the end) offers his assistance for not much pay. What could go wrong? The hardened, army-defector heroine who has laid waste to countless worlds with her martial prowess and superior tactics seems to be entirely clueless on how this is probably a trap. She seems to oscillate quite substantially between a hopeful but dangerous protector and a naïve idealist who sees the best in others. This schism in her personality leads to quite a few questionable plot moments, such as this one. She was seemingly written to be the naive farm-girl, akin to Luke Skywalker, before the writers back-filled her story to have a military background. They clearly didn’t care about continuity.

Where do I get the indentured servant work-out routine?

Now, we’re in a heist movie! Meet Tarak (Staz Nair), a walking chosen-one archetype who is enslaved on a planet for unnamed reasons and is absolutely shredded (apparently indentured servitude is great for your abs). It’s a knock-off of Anakin on Tatooine, but at least this time the alien slaver isn’t an antisemitic cartoon.

The slave owner proposes the same gamble that Neeson’s Qui-Gon Jin makes in Star Wars: The Phantom Menace, but instead of a pod race to seal their fate it’s the taming of a griffin. Not one of the characters speaks up to agree or disagree to this proposal, including the thief who is later revealed to have an ulterior agenda the entire time. All we get is a short “Can you ride it?” and the response “I can ride it,” between two of the stakeholders in this gamble, without so much as a word to the others. Let’s have a moment of silence for the potential character moments we could have been given in a better film.

I’m not a Star Wars fanatic, but the parallels with Episode One here are clear. Sadly, Star Wars was more exciting, which is not one of the words I would normally use to describe Star Wars Episode I.

Personal Note: The griffin doesn’t get to escape with the main heroes after forming a bond with one of them, which is lame. I can only assume this is due to the VFX budget because there was no reason not to bring it along. Also, to ride the griffin you need to bow to it in respect. A certain British YA author/billionaire would like a word.

A hero’s journey was being attempted, with the stubborn heroine initially refusing to be thrust into a new world, but we’ve fully shifted gears to a “collecting-the-team” heist montage. Here, we find another issue with the script: low stakes and no emotional ties to said stakes or characters.

Throughout the film, the heroes recruit rebels to their cause with the laughable context of defending a single small farming village on a single small moon. There is surely nobility in defending those people, but narratively that’s not enough. The audience is not introduced to anyone in the village that would tie them emotionally to its destruction, aside from one farm girl, and Kora herself is shown to be a sort of outsider with no real ties to the community. Why should we care, then? The film has no answer for us.

Next on our heist movie montage, we’re on a “mining planet” (sci-fi trope!). The establishing shot of the planet is so visually cluttered that I actively looked away from the screen. This is not what I meant by “show, don’t tell”. There is a way to convey overdevelopment, excess, and brutalism without making the audience’s eyes hurt. Rather than conveying those aspects, which was likely the purpose, the shot conveys cheap and shallow worldbuilding using hasty VFX.

An assault on my eyes to “dramatic music.”

Personal Note: There is no need for the naming of places, which the film does dutifully for each new location, as they’re not memorable, consequential, or even relevant to the story. I can’t even remember the name of the moon the film starts and ends on. (Is it Rebel Moon? It’s got to be Rebel Moon.) Any amount of time could’ve been cut from the beginning of the movie to allow these locations to breathe, but apparently the depiction of a young girl almost being molested by soldiers was more appealing to the writers than the development of central characters.

On the mining planet, Shelob a spider alien takes a child hostage. The spider is upset with how the planet has become a dystopic mining colony, and she’s just now airing these grievances despite the planet looking like it’s been colonized for several hundred years, and she’s doing it to innocent people who aren’t in charge and are just as miserable, and she explains the entire thing instead of letting her actions be interpreted by the audience, and and and… It’s possible that the spider alien isn’t a reference to the many giant arachnids of fiction, such as Tolkien’s Shelob or Rowling’s Aragog. Based on the absolutely derivative nature of the film so far, I am forced to doubt this.

A swordswoman named Asajj Ventress Nemesis uses dual red lightsabers glowing molten swords to kill the spider alien. This could easily have been a quick flourish to show the audience her mastery but was instead made into a several minute brawl to pretend like there was a chance she didn’t win. She does win, of course, but expresses that this is a tragedy, to showcase her deep inner turmoil of being a killer but valuing all life. Get it? Like a jedi, or a samurai? She does this using words instead of acting or mood, because how would the audience know if it wasn’t said aloud? I should mention here that I don’t blame the actors for the script. And, of course, we have another clear scene which was likely part of the original Star Wars pitch of the script.

It was at this point that I may have fallen asleep, but I refused to rewatch it. I’m quite sure the band of outcast rebels travels to a planet with the Roman Colosseum plopped down in the middle. Oh, and there’s a Djimon Hounsou character named Titus. I respect the hell out of that man for taking whatever acting job pays him. Get your bag, king.

Speaking of kings, there’s a king (named after a font?) who is housing a rebel group. Here, the film starts veering dangerously close to Mel Brooks parody with names like Levitica and BloodAxe and plodding plot points that no one cares about or understands. I would almost prefer that the film be a parody.

The politics of this universe are also beginning to unravel for the audience, because I was under the impression that the king, queen, and princess were important, though they’re dead. Yet here we have King Leviticus of some other planet. How many planets have monarchies, and why do we care about the dead king if there are other kings? Why is it called the Motherworld if this is clearly a patriarchy and not a monarchy? Why is this film more than 2 hours long?

Mr. Bloodaxe himself.

One of the BloodAxe siblings decides to help the Rogue One crew group of rebels after giving a speech to his army. The speech blandly tells the audience everything that could otherwise have been gleaned from mood-setting score, acting, context, or plot (all of which are notably absent).

The main group arrives at one last banal location where they’re inevitably betrayed by the thief (Charlie Hunnam) and sold out to the forces of evil. But wait, what’s this? A character moment for the farmer whose name I’ve forgotten (Gunnar)! In the only moment of the movie where an actor doesn’t speak their intentions out loud, narrate, or otherwise insult the audience’s general intelligence: Gunnar kills the thief. This moment only proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that none of the notable actors, which have all been killed off (save Hopkins, who likely did his VO in the comfort of a booth in a single day) were willing to do this for multiple films.

A battle ensues where most of the BloodAxe forces and the BloodAxe brother are bloodlessly axed from the film via laser cannons, which was quite disappointing given their name. There’s a painfully long sequence where Kora fights Skrein’s villain, Noble, and neither of them seem to take any meaningful damage. This is more reminiscent of a video game boss-fight than a film. As an avid gamer, I’d argue there’s a reason for that length in video games, such as allowing a player to express mastery or creativity, and providing meaningful challenge. In film, there is never a reason to drag fights out unless there is some meaningful storytelling taking place – there is none, so the audience is left wondering when the film will end while their eyes glaze over.

Finally, the villain is killed, and the heroes win. Right? Sort of.

In one of the least surprising moments of the film, but still just as hurtful to my feelings, Snyder lets us know that he deliberately wasted our time during that final fight. The villain is still alive because of space magic and bad writing. Paying homage to the much beloved and critically acclaimed Last Airbender film by M. Night Shyamalan, as well as Stefen Fangmeier’s Eragon, Snyder takes this moment to reveal the “true villain of the story” in the final moments. It’s the Regent Belisarius, who we’ve met before in flashbacks.

Personal Note: This is quite obviously a masterful stroke of storytelling by Snyder, which I’m sure will go down in history as one of the most memorable moments in cinema and redeems the entire film. I can’t wait for more! *Punches hole in wall*

Here lies my last brain cell, may he rest in peace.

The Regent scares Noble with oddly specific and clunky dialogue that sounds less like a threat and more like something out of Anchorman’s news-crew brawl. The heroes go home, having learned absolutely nothing they didn’t already know and having gathered 4(?) more people on space horses to help their little space village fight the space equivalent of an aircraft carrier. Oh, and in true exposition-dumping form, Djimon Hounsou gives a monologue about why their victory was meaningful, so the audience doesn’t have to think too hard – or at all.

And finally, PART ONE ends. Somebody go put Zack Snyder on time out. And get me a spackle knife for my wall.

It’s become abundantly clear that nobody in the studio pipeline at Netflix, the production companies associated with this film, or Zack Snyder and his fellow writers are expected to perform any sort of quality control on a screenplay. To expect quality, however, would be to ignore the clear conceit layered into the script. The writing self-aggrandizes its own mythology and cleverness, but continuously ignores basic film-making lessons with such fervor that I fear any critique will fall on deaf ears. If this and Matt Rife’s flat standup routine are what we can expect from Netflix Original writing going forward, I have no problem cancelling my subscription entirely.

Alternative Review of Rebel Moon, Part One: A Child of Fire as an incidental satire on excess, maximalism, patriarchy, the current state of Hollywood’s writing scene, and a parody of Disney’s treatment of the Lucasfilm properties:

Excellent, no notes.